How To Be a Hero for Dyslexic Audiences

I’ve loved comics since second grade. I fell in love with some of comics’ greatest heroes— Spiderman, Batman, and Superman—through their movies and animated shows, and with time I grew to love other characters, like the working-class magus John Constantine from the Hellblazer series and Green Lantern villain Sinestro.

In comics, there are tons of characters to explore—a vast variety of powers, personalities, origins, and countless other traits that make them both awesome and relatable. But it’s taken some time for the world of mainstream superheroes to adequately reflect our changing times and the diversity inherent in our daily world.

One of Marvel Comics’ oldest superheroes, Black Panther, is now a household name thanks in part to the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The industry standout Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse helped make Miles Morales just as popular—or maybe even more so—than Peter Parker, Marvel’s first Spiderman.

One of DC’s most popular occult characters—the abovementioned John Constantine—is canonically bisexual and, in his long-running horror series published by DC Comics’ offshoot Vertigo, helped explore serious contemporary political and cultural problems, like Margaret Thatcher’s far-right conservatism in the United Kingdom and anti-gay fearmongering during the AIDS crisis.

With new writers and creators, new characters—or new takes on existing ones—and with an eye on the importance of inclusion and diversity in comics, there is an ever-growing world to explore—a world made all the richer by its ability to echo real people of all backgrounds, cultures, and identities.

Despite the vast amount of time I spend with comic book characters, it recently dawned on me that I didn’t know of any who shared a particular trait with me—were there any heroes with dyslexia around, perhaps rubbing shoulders with the likes of Batman or Wolverine?

While the precise causes of dyslexia are still unknown, researchers have established that, in general, dyslexia is the “result of individual differences in areas of the brain that process language” (Mayo Clinic). According to the International Dyslexia Association, “anatomical and brain imagery studies show differences in the way the brain of a person with dyslexia develops and functions,” compared to the brain of someone without dyslexia.

As research into the human mind continues, we are likely to find out more about dyslexia, but, for now, it can best be summarized as a neurodivergent learning difference, primarily affecting a person’s ability to read and say words out loud.

Not everyone with dyslexia experiences it the same way, or to the same degree. Additionally, dyslexia is far more common than some might think: “perhaps as many as 15–20 percent of the [U.S.] population as a whole…have some of the symptoms of dyslexia” (Dyslexia Association).

(Image source: Marvel Comics.)

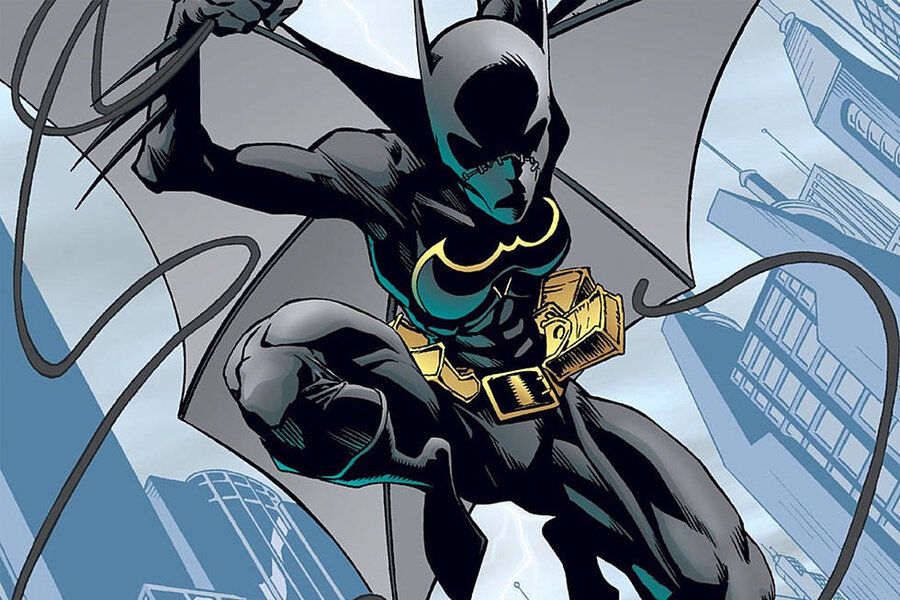

(Image source: DC Comics.)

Recently, I started to look online for comic book characters that had similar symptoms and experiences. A little bit of research led me to Marvel’s Takeshi “Taki” Matsuya—a mutant hero with the ability to psionically control machines—and DC’s Cassandra Cain—the fourth character to adopt the mantle of Batgirl.

Taki and Cassandra are some of the few American comic book superheroes of East Asian descent, but they also seem to be the only two with dyslexia. The symptoms and types of their dyslexia are vague.

Taki has “trouble reading” but is a “boy genius,” while Cassandra has been diagnosed with the oddly labeled “extreme dyslexia.” This seems like a huge missed opportunity to both reflect dyslexia in a more realistic way and to some extent discuss the nuances of this learning difference.

Dyslexia can be layered and individual symptoms vary greatly, but there are five established, distinct processing differences that can help us understand what’s going on in a person’s mind:

Phonological Dyslexia: This kind of dyslexia is the most common, according to NeuroHealth Arlington Heights, and deals with “difficulties in matching sounds to symbols and breaking down the sounds of language.”

Symptoms of phonological dyslexia can include difficulty learning sounds made by letters and letter combinations, sounding out new words, recognizing familiar words in new contexts, and slow reading.

Rapid Naming Dyslexia: Individuals with rapid naming dyslexia have difficulty “quickly naming things such as numbers, letters, and colors on sight,” according to the Learning Lab. This condition is also known as rapid naming deficit and can be present in people who don’t have dyslexia.

People with rapid naming dyslexia may take longer to name numbers, letters, or colors in a row, “which could be related to processing speed” (the time it takes for a person to do a mental task).

Double Deficit Dyslexia: People with double deficit dyslexia have difficulty with both “naming speed and identifying the sounds in words” – a combination of both phonological and rapid naming dyslexia. This kind of dyslexia can materialize through a slower naming speed rate when asked to recall words, as well as weak phonological awareness.

Surface Dyslexia: Surface dyslexia is marked by the difficulty to say words that are not voiced out, or read, the way they are spelled. According to the American Psychological Association, surface dyslexia is also reflected by difficulty “in recognizing whole words and…an overreliance on sounding out words each time they are encountered.”

Symptoms of surface dyslexia include difficulty with spelling, reading words that don’t sound the way they are spelled, and difficulty reading new words by sight.

Visual Dyslexia: Affected by visual processing, this type of dyslexia makes it so that an individual’s brain doesn’t receive the complete picture of what the eyes see. According to NeuroHealth Arlington Heights, “visual dyslexia will affect the ability to learn how to spell or form letters because both require the brain to remember the correct letter sequence or shape.”

Symptoms of visual dyslexia include blurry text, text going in and out of focus, difficulty tracking across lines of text, and difficulty keeping one’s place on a page of text. People with visual dyslexia may also be affected by headaches or eyestrain.

I’m a person with dyslexia, and as a communications professional, my symptoms are top of mind. Growing up in Ukraine, I spoke Russian until about the age of 7, when I had to move to Virginia and, consequently, learn English.

I never had too much trouble with reading or writing—in fact, English and literature have always been some of my favorite subjects in school—but as I started to notice my dyslexia, I understood that some of my occasional problems with reading—such as keeping track of where I am on a line of text—were in fact related to this learning difference.

In time, it dawned on me, too, that my persistent difficulties in math classes from middle school to college were caused in part by my dyslexia—it has always been difficult for me to mentally keep track of numbers or to quickly grasp the relationships between sets of numbers.

Thinking back, the only math class I wasn’t terribly uncomfortable in was geometry, and that’s probably because—as a visual learner—the various numbers (that in my mind still feel arbitrary and nebulous) were more or less grounded with the help of shapes and pictures.

Frankly, it would have been helpful to see these issues back then with the knowledge and experience I have now, but it’s also true that “it’s better late than never.” At least now, I am better equipped to understand and respond to my own learning challenges and needs, which is really a lifelong skill to practice.

•

It continues to be our job, as responsible content creators, to acknowledge dyslexia, among other challenges and needs, and ensure that our work responds to those with this learning difference.

Ensuring that one’s online content complies with digital accessibility best practices is more than just a legal requirement—it helps reach a wider audience and works to engage everyone in the conversation.

There are many small steps you can take to make a website more accessible, such as creating alternative (or alt) text, making sure that each page has strong color contrast for visually impaired users, and grouping information in a way that makes the overall presentation easier to follow.

Below are some ideas from the Bureau of Internet Accessibility to help you get started on making your content more accessible for users with dyslexia:

Font choice: Creators can make their text more legible by “choosing a common, basic font.” Sans serif fonts—like the clean, iconic font Helvetica—are “considered better for accessibility, since they can be displayed on smaller screens without crowding letters together.” Lucida Sans, Verdana, Arial, and Tahoma are good choices, too, and some fonts have been specifically created for people with dyslexia, like Read Regular, Lexie Readable, and Tiresias.

Break down paragraphs: In addition to the fonts you choose, it’s just as important—or even more so—to “break up paragraphs into smaller ‘chunks’ of content,” maintaining a consistent appearance throughout.

Be mindful of your images: It’s generally good to avoid images that have text in them. The Bureau of Internet Accessibility notes that “some users may zoom in on content to improve readability, and pictures of text may not scale appropriately.” However, this doesn’t mean you should be shy when it comes to using visuals—just mindful.

A multimedia presentation, using graphs, photos, and even videos, can “provide people with another way to understand your message without reading through every line of text.”

In this ever-changing digital landscape, these methods—and many others—are something all content creators should strive for.

People with dyslexia should feel invited to contribute their thoughts and skills to society. After all, our strengths, among many, are creativity, analysis, and problem-solving.

Through activism, instant communication, and the internet, the world keeps getting bigger—which is a good thing. Maybe with time, there will be more superheroes with dyslexia for people to connect with at their local comic book stores.